What’s causing inequality in STEM, and is skills-based hiring the solution?

It’s well-known that STEM industries – industries under the umbrella of science, technology, engineering, and math – are some of the least diverse industries out there.

Despite that the skills needed for a software engineer are not inherent to any race, gender, or other demographic categories, 93% of professional developers are men, more than 40% are White, and more than 98% do not have a disability.[1]

Given that more than 90% of organizations that switched to skills-based hiring in 2022 saw an increase in diversity, it’s understandable for STEM leaders to consider skills-based hiring as an antidote – but can it work?

This blog explores the different diversity issues plaguing STEM industries and how skills-based hiring can help.

Table of contents

- What does it mean to have a career in STEM?

- What’s the inequality in STEM fields?

- What’s causing inequality in STEM jobs?

- How can skills-based hiring fix inequalities in STEM?

- 5 skills-based strategies to address inequalities in STEM

- Use a data-backed method to reduce inequality in STEM by switching to skills-based hiring

What does it mean to have a career in STEM?

STEM isn’t so much a single industry as a collection of specialties.

The skills required for a career in STEM fall under science, technology, engineering, math, or a combination.

Naturally, many industries and roles overlap these areas. A data analytics position for a HealthTech app is a good example of a role with industry crossover.

STEM workers represented almost a quarter of the total US workforce in 2019. More than half do not have a bachelor’s degree and work mainly in healthcare (19%), construction (20%), installation, maintenance and repair (21%), and production (14%).[2]

Here are some more examples of careers in STEM and the skills required in each area:

Skill area | Example roles | Example skills |

Science | BiologistGeneticistLand surveyor | ObservationAbility to apply scientific methods |

Technology | Data scientist Software developerHardware technician | Data analysis Problem solving Coding languages |

Engineering | Mechanical engineerCivil engineerHealth and safety engineer | Problem solving Design Mechanical reasoning |

Math | Economist Business analystAccountant | Numerical reasoningData analysisStatistics |

What’s the inequality in STEM fields?

So far, we’ve only briefly touched on the issues of inequality in STEM. But, as with any big problem, you need to understand it to solve it.

Let’s dig deeper into the inequalities in STEM industries and how they affect different groups.

Women

Women’s share of STEM jobs varies slightly depending on how you define “STEM” because some measures do not include low-paid health workers like nurses and healthcare assistants.

These roles overly-employ women, according to Pew Research Center.[3]

Indeed, there are so many women in nursing that it has become a “pink-collar job.”

Nursing is one of many women-led roles under the HEAL umbrella (jobs in health, education, administration, and literacy).

Often, we define HEAL as the opposite of STEM. Men’s underrepresentation in HEAL roles is drastic.

However, most measures of women in STEM agree that although they are still the minority, women have gradually increased their share of higher-profile healthcare jobs over time.

One example from the healthcare industry is the increase in the number of women surgeons.

Women have also increased their share of STEM occupations in the past 50 years.

According to US census data, the percentage of women in STEM has risen from just 8% in 1970 to 27% in 2019.

Although women’s representation is increasing, the differences in the kinds of roles that women occupy in STEM – like low-paying healthcare and administrative roles – mean that there’s still a large gender gap when it comes to compensation.

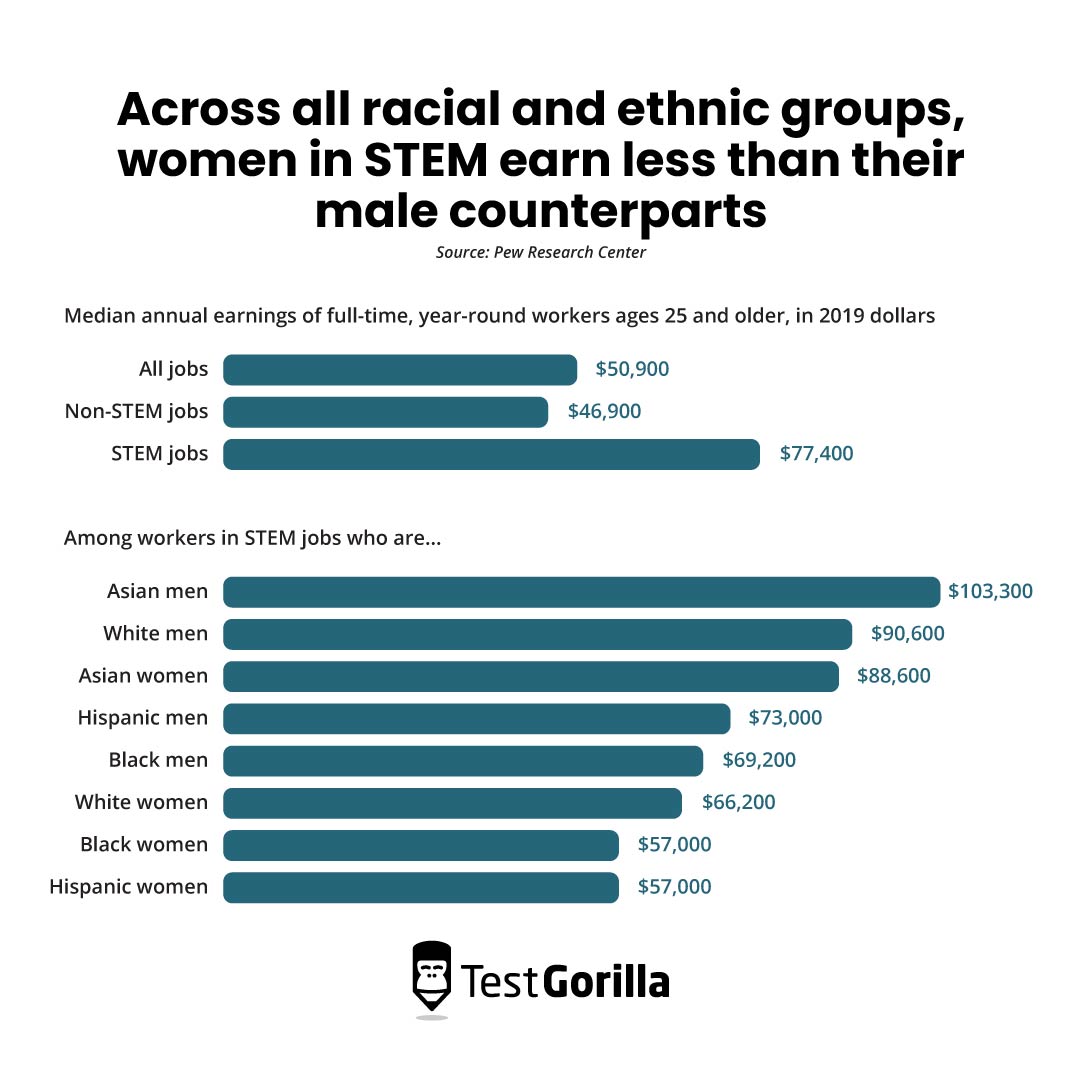

The Pew Research Center study above found that across all ethnic groups, women in STEM earn less than their male counterparts.

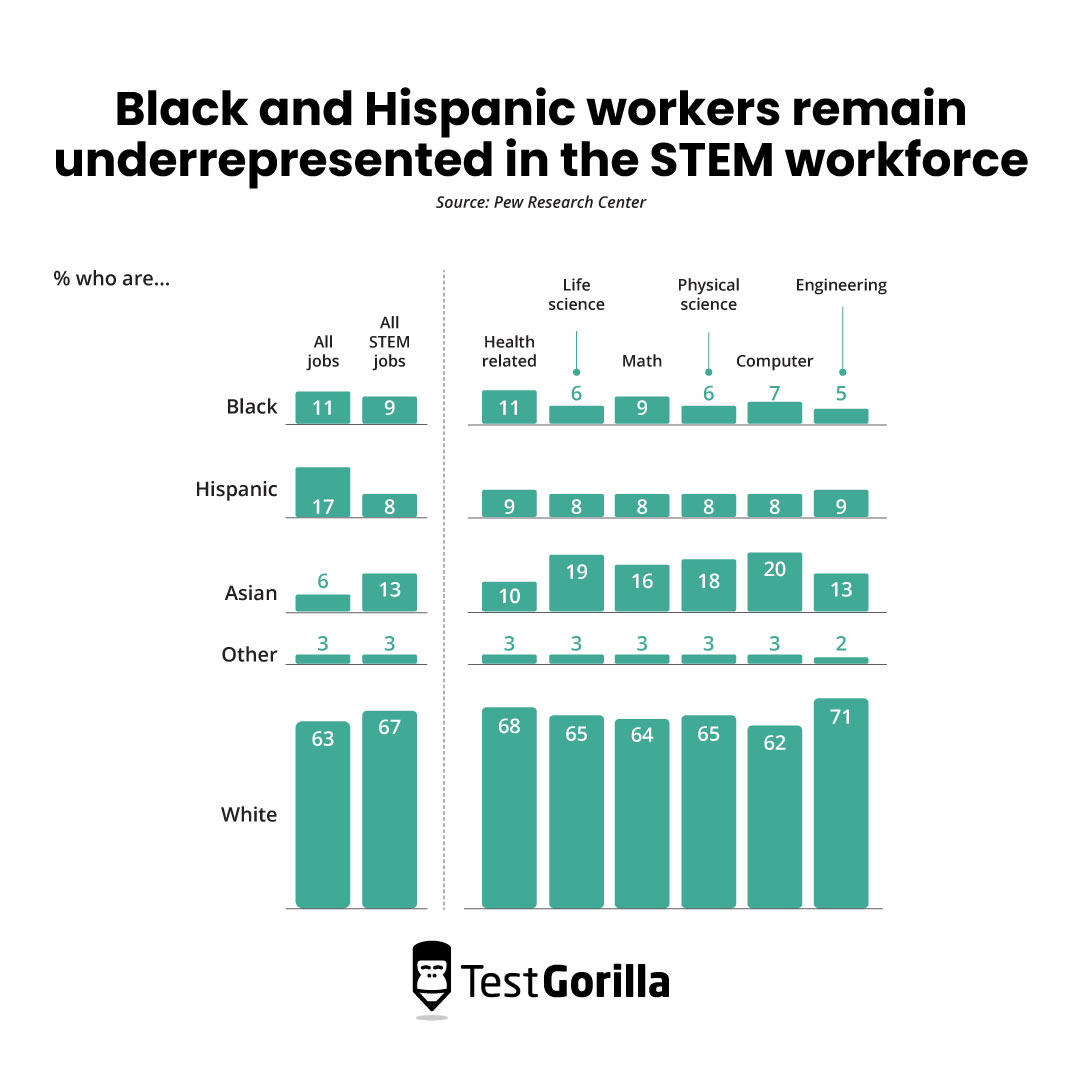

People of color

The gender pay gap in STEM roles is similar to the pattern observed among people of color in STEM.

Although Pew’s research shows that Asian workers are overrepresented in STEM and even garner the highest-paying jobs, other racial minorities feature in less lucrative STEM roles.

For example, health technicians and nursing roles have some of the largest shares of Black or Hispanic workers.

More than a third of licensed practical and vocational nurses are Black or Hispanic.[3]

Disabled workers

STEM fields also don’t include many disabled people.

Although the research is less extensive in this area than for racial and gender disparities, one study found that scientists and engineers with disabilities are more likely to be unemployed.

Moreover, their unemployment rate was higher than the overall US unemployment rate in 2019.[4]

LGBTQ+ workers

Workers who belong to the LGBTQ+ community also experience disadvantages in STEM.

LGBTQ+ individuals are 20% less likely to be represented in STEM roles than expected from their share of the population.

They are also more likely to report negative workplace experiences than their non-LGBTQ+ colleagues.[5]

STEM job stereotypes include that it’s “men’s work,” which discourages non-male-identifying people from taking up STEM roles.

It also means that LGBTQ+ men who get involved in STEM face prejudice owing to societal prejudices that label them as “not masculine enough.”

Research supports this hypothesis.

According to a study by the American Physical Society, around 15% of LGBTQ+ men, 25% of LGBTQ+ women, and 30% of gender-non-conforming individuals working in physics said they felt uncomfortable or very uncomfortable within their department.[6]

Further research reveals that LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely than their peers to experience career limitations, devaluation of their skills, and even harassment at work.

They are also more likely to report health issues and the desire to leave STEM altogether.

These trends remained consistent across STEM disciplines and sectors and did not vary with individuals’ education level, work effort, or commitment to their roles.[7]

Intersectional disadvantages

Like STEM, each category above does not describe discrete “types” of people but different attributes that can and do overlap in many people.

Understandably, individuals who exist at the intersections of these categories – for instance, disabled women or LGBTQ+ people of color – face multiple barriers simultaneously.

The data reflects the added difficulties this intersectional disadvantage can bring.

Hispanic and Black women experience the largest pay gaps compared with White and Asian men, with Hispanic women earning barely more than half of the median annual earnings of Asian men in STEM.[3]

What’s causing inequality in STEM jobs?

We’ve examined the data – what we call the symptoms of the inequality issues in STEM.

But what’s causing these disparate outcomes for marginalized workers?

The way we see it, there are three key causes of inequality in STEM jobs.

1. Inequalities in STEM education

STEM highly emphasizes academic learning, as a field that relies heavily on technical skills. Undoubtedly, schools introduce many skills required for STEM careers.

However, educational inequality means the marginalized groups discussed above are more likely to encounter educational obstacles.

Inequality reduces their access to key skills and qualifications, diminishing their likelihood of pursuing a career in STEM.

Take the example of racial inequality.

Over and over again, studies show that children of color, particularly those from low-income backgrounds, are more likely to be disciplined by educators for the same behaviors tolerated in their White classmates.

Their punishments are also more likely to disrupt their schooling. Suspension and expulsion are more common among children of color, with this trend starting as early as preschool.[8]

Other marginalized groups also experience barriers to education.

Just one-fifth of students from low-income families make it to college, and disabled students are less likely to complete bachelor’s degrees than their able-bodied classmates.[9][10]

Men who identify as gay, bisexual, or “other” are 12% less likely to complete an undergraduate degree in STEM than heterosexual men.

Interestingly, however, the same cannot be said for women. Their sexuality does not impact their likelihood of completing a STEM degree.[11]

The underrepresentation of certain groups in STEM is partly down to the gendering of STEM as “for boys” subjects.

Thus, girls could lack confidence in their own STEM skills.

Research shows that even when girls’ and boys’ performance in STEM subjects, use of STEM-based resources, and participation in STEM-related extracurricular activities are equal, boys are more confident in their STEM skills than girls.[12]

This lack of confidence can further impact students’ STEM participation as they age.

Although there is no measurable gap in science aptitude between boys and girls in fourth grade, by 12th grade, this widens by three points on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scale.

The same study shows that Black students’ science scores drop by five points compared with two points for White students between fourth and 12th grade, and students living in high-poverty areas have lower average scores than those in more affluent areas.[13]

All this contributes to application gaps in STEM roles – in other words, differences in the numbers of STEM applications from different groups.

2. Lack of diverse role models

The above issues create a self-perpetuating problem.

Without diverse individuals embracing STEM and going into STEM careers, the popular understanding of what a STEM worker “looks like” remains the same.

This lack of diverse role models greatly impacts marginalized individuals’ willingness to engage in STEM careers.

One study by Microsoft found that the number of girls interested in STEM almost doubled when exposed to role models.

Girls with role models also displayed more passion for STEM and were more able to imagine themselves working in a STEM career.[14]

Indeed, research into STEM candidates across many intersections recommends elevating diverse role models as one of the key ways to promote diversity in STEM.

3. Discrimination in the job market

As we’ve seen, many of the gaps in the STEM workforce open up long before aspiring STEM workers make it to the job market.

Much of this is because of the over-emphasis on four-year college degrees as a skills marker across STEM industries.

Since not every student gets an equal chance to attend college, and with this key barrier to entry in place, it’s no surprise we see little diversity in STEM.

Moreover, even among college-educated workers, candidates from marginalized backgrounds are less likely to work in the same STEM field they majored in.

Women who majored in computer science or other computer fields are less likely than their male peers to work in the tech industry.

Similarly, women engineering majors are less likely than their male classmates to work as engineers after college.[3]

This situation partly results from unfair hiring practices that enable unconscious bias to influence hiring decisions and disadvantage marginalized workers.

Traditional hiring relies heavily on the “gut feeling” of hiring managers when shortlisting and interviewing candidates.

This “intuition” is often influenced by unexamined bias.

Unconscious bias is especially problematic when hiring for STEM roles, which are strongly associated with a certain “type” of person.

Other, less obvious biases can creep in, too.

For example, Harvard Business Review cautions recruiters against preferring unpaid internships over other summer jobs, which introduces socioeconomic bias.

They also note that many employers believe, without the data to support this, that minority and female candidates are less likely to accept job offers because they’re in higher demand from other firms.

Candidates with disabilities also face invisible barriers.

In academic settings, many programs required for qualification in STEM roles use vague terminology around physical abilities, which stops disabled students from qualifying and participating professionally.[15]

Disabled workers could also face skepticism and mockery from employers.

A recent example comes from Twitter, where Elon Musk caused controversy by openly mocking a disabled employee and accusing him of using his muscular dystrophy as an excuse for doing “no actual work.”

When supplied with a list of tasks the employee had done, Musk replied, “Pics or it didn’t happen.” (He later apologized.)[16]

How can skills-based hiring fix inequalities in STEM?

STEM industries need change to access the many benefits of diversity in the workplace.

We believe that skills-based hiring methods are the way to achieve this.

Here’s how:

Expanding the talent pool to address the “STEM shortage”

Hiring managers everywhere are trying to expand their talent pool, but this is an especially pressing issue in STEM.

There’s a global skills shortage across industries, with three-quarters of companies worldwide reporting talent shortages – the highest figure in sixteen years.[17]

These shortages exist in STEM areas, especially technology.

Employers are currently experiencing a war for talent in tech, with 70% of companies reporting skills shortages in technical areas.

Thinking you should hunker down and wait it out? Think again.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of jobs in STEM is en route to outpace growth in other industries by 2031.

This situation suggests that you should urgently increase the number of job applicants you consider for roles.

One way of doing this is to remove the barriers that obscure hidden workers from your hiring process.

You can use skills testing to screen candidates for employment rather than outdated measures like degree requirements and resume evaluation.

Crucially, with skills testing, you can expand your talent pool without doubling your workload.

You can even expand your search overseas without needing to research and vet international candidates’ education and experience, because skills tests directly assess their key skills and automatically rank them against domestic candidates.

Reducing unconscious bias

Despite a reputation for being rational, scientists are just as likely to display interviewer bias as any other hiring professional.

Don’t believe us? A study at Yale University found that even when they had received training about objective hiring, male and female scientists still preferred to hire men.[18]

Other types of bias also flourish in traditional hiring.

For example, a recent study found that applicants with White-sounding names were 9% more likely than those with Black-sounding names to receive responses from employers, even with identical applications.[19]

We don’t believe this occurs out of malice on the part of hiring managers most of the time.

Rather, a lack of objective data on which to base hiring decisions can lead to recruiters using their “gut feeling,” which is usually informed by bias.

Implicit bias training doesn’t work to increase diversity, however. Instead, give recruiters support for data-driven decision-making.

Skills testing gives you this data by objectively testing each key skill area for the role and automatically sorting candidates based on their performance.

Successfully removing bias in hiring does not, on its own, produce equality of outcome.

What it produces is equality of opportunity. Combined with wider-reaching policies to push for equality outside of the workplace – for instance, in education – this moves us toward a more representative STEM world.

Still, you are likely to see significant benefits from increased diversity.

A study of more than 2,000 successful hires found that the number of women hired into senior roles increased by almost 70% when recruiters used skills-based hiring methods.[20]

Even this limited change in diversity can transform your business outcomes. Deloitte research has found that diversity of thinking increases innovation by around 20%.[21]

Diverse teams can also help avoid mistakes, especially in tech.

Remember the case of the automatic soap dispenser that couldn’t recognize Black skin? Just think how easily a more representative team could have avoided that unfortunate oversight.[22]

Giving employers the tools to bridge skills gaps

Finally, a skills-based approach gives you the tools to expand and adapt your workforce by identifying and addressing internal skills gaps.

Addressing skills gaps is essential in STEM because the fast pace of technological change largely causes the global STEM skills shortage.

People in STEM regularly need new skills, and old ones quickly become obsolete, meaning that even the most highly-skilled employees require upskilling at some point.

By paying greater attention to employees’ development needs from the start of their employment, you can ensure they receive the proper training needed to advance.

Training promotes diverse candidates up the corporate ladder without turnover owing to lack of opportunity – the number one reason people left their jobs in 2019.[23]

Digging into skills data for the underrepresented STEM workers you have is one of the strategies the National Science Foundation recommends to increase diversity in STEM.

This helps you better understand their needs and keep them in your organization.

Increasing retention brings numerous benefits.

When surveyed, 93% of chief executive officers who introduced upskilling programs reported increased productivity and resilience in their workforce and improved talent acquisition and retention.[24]

5 skills-based strategies to address inequalities in STEM

So far, we’ve covered:

The state of inequality in STEM

Where these inequalities in STEM come from

How skills-based hiring methods help

Now, it’s time to consider actionable strategies that can help improve diversity in your STEM workforce.

5 ways employers can address inequalities in STEM: Summary table

In a hurry? Here are the highlights:

Skills-based strategies to address inequality in STEM | Example actions |

Reach out to get young people involved in STEM | Conduct outreach workshops in schools with diverse employees from your company |

Remove degree requirements from job postings where possible | Scrap degree requirements for web developers and implement standard upskilling for every employee |

Use skills testing to screen and shortlist candidates | Allow disabled candidates to use more accessible versions of skills tests |

Implement inclusive working practices | Use flexible work to be more inclusive of disabled employees and caregivers |

Use an internal talent marketplace to promote fairly | Determine internal promotions based on skills levels rather than the subjective opinions of hiring managers |

1. Reach out to get young people involved in STEM

Inclusivity is a growth engine for more than just businesses.

It can benefit society at large, so employers in STEM should push for and participate in STEM education reform.

Participation has the dual benefit of bringing greater access to opportunities for diverse students and opening up the STEM pipeline to fill skills gaps.

Providing students with diverse role models for what STEM workers look like is a great first step.

For example, seeing women in leadership positions is greatly encouraging for marginalized candidates: 65% of women and 66% of non-binary people in Gen Z say it makes them more likelyto apply for a role.

As an employer, you can access these role models within your workforce.

Encourage your leaders to participate in mentorship programs, set up internships, and organize work experience days for students of diverse backgrounds.

You can even run outreach workshops with schools to introduce STEM careers as an option to more students.

When doing this, emphasize STEM’s opportunities for creativity and making real change in the world because these factors matter to women and girls considering STEM careers.[25]

An example of these policies in action is IBM’s Skills Build program, which offers online training courses to college students.

This approach democratizes STEM skills training and creates the STEM skills the organization wants to see in the market.[26]

2. Remove degree requirements from job postings where possible

Many employers assume that STEM roles are exempt from the widespread degree “reset” phenomenon that has led employers across industries to scrap degree requirements, particularly for entry-level roles.

However, this perceived exemption is an illusion.

Because of the rapid pace of change in STEM industries, degrees could have even less longevity than in other fields.

One study found that, although STEM degrees have an initially high economic return, it declines by more than 50% within a decade of graduation.[27]

An analysis of 26 million job postings also found that college grads exhibit lower engagement levels than their peers, as well as higher turnover rates.[28]

STEM degrees have dubious value, and many STEM careers don’t require degrees at all.

Many web developers, for example, are entirely self-taught. Engineers also have paths to employment that don’t lead through higher education.

Advanced engineering work can require specific qualifications and licensing, but in the US and other places worldwide, many early- to mid-level engineering roles are accessible via on-the-job training.

This situation is clear by the number of companies scrapping degree requirements in STEM.

Just 26% of Accenture’s Software QA Engineer postings require a degree, and less than 30% of IBM’s do. However, many organizations like Oracle, Intel, and Apple still overwhelmingly ask for college grads.[29]

Scrapping degree requirements opens up your talent pool to STARs: candidates who are “skilled through alternative routes.”

They include self-taught web developers and engineers who learned through apprenticeships.

Opening up the job pool gives you access to more talent – and unsurprisingly, given the inequality in education we’ve observed above, more diverse talent.

For best results, provide upskilling opportunities as a “given” for every employee to ensure that candidates with and without degrees keep their skills up to date.

3. Use skills testing to screen and shortlist candidates

STEM industries increasingly use skills-based hiring for many of the reasons we’ve already outlined.

It minimizes unconscious bias and hiring discrimination by giving hiring managers objective data to support their decision-making.

It also broadcasts your fairness to candidates, which can help close application gaps.

Research suggests that when tech companies use skills-based hiring, the number of women candidates increases threefold.[30]

Skills testing is also often a more accessible option for disabled candidates, especially when you offer additional accommodations, such as extended test times or the option to take the test in a different format.

You can use culture add testing to ensure your push to diversify doesn’t create a fractured working culture.

Our Culture add test enables you to evaluate how prospective employees match up with your deeper organizational values while still bringing something new to your workforce.

4. Implement inclusive working practices

Inclusion doesn’t stop at the point of hiring. Harvard researchers recommend taking an intersectional approach to inclusivity that includes marginalized individuals in decision-making and works to remove both:

Barriers to access

, which stop marginalized individuals from getting into the organization.

Barriers to success

, which stop marginalized people from progressing through the organization.

[31]

So far, we’ve covered how employers can dismantle barriers to access. Inclusive working practices tackle barriers to success. One of the most effective inclusive working practices is implementing flexible working practices. Many tech workplaces are already on board with this, and for good reason. More than half of STEM candidates rate flexible working as second only to compensation and benefits when it comes to hiring incentives.[32]As well as being popular, flexible working policies are key to disability inclusion in the workplace. They enable employees with a wide range of health issues to manage their care more freely. For instance, employees can use flexible working to fit their work around healthcare appointments or manage chronic conditions.The same advantages also make them inclusive of caregivers, who are statistically more likely to be women.The key is to follow remote work best practices to ensure you avoid remote worker discrimination. Remote worker discrimination is when out-of-office workers receive fewer opportunities for development and advancement than their in-office peers.It’s rife in many workplaces. More than 40% percent of supervisors say they sometimes forget about remote workers when assigning tasks, and more than a third of remote employees say permanently working remotely would limit their career growth.Finally, be mindful of the language you use in the workplace. For instance, be more inclusive of LGBTQ+ employees by training your workforce to:

Avoid gendered language – for instance, using “they” instead of “he or she” in company memos.

Replace gendered job titles like “salesman” with gender-neutral ones like “sales representative.”

Use gender-neutral terms to refer to families – for example, “partner” instead of “husband or wife” and “parental leave” instead of maternity leave.

Always use employees’ preferred pronouns and encourage employees to display their pronouns in their email signature.

5. Use an internal talent marketplace to promote fairly

Finally, using the data you collect from recruits during the hiring process and from your current workforce, use an internal talent marketplace to make fairer promotion decisions.An internal talent marketplace is a piece of software or a spreadsheet showing you all of the skills available in your organization. It makes conducting a skills gap analysis easier by displaying the areas in which core skills are missing.It also applies many benefits of skills testing for external hiring to internal promotion decisions. For example, it enables you to see objective data about whose skills are the best match for an internal promotion opportunity rather than relying on your own subjective assessment.This kind of subjective promotion can hinder success for many groups, such as women. Research shows that women are less likely to get promoted than their male colleagues, despite being less likely to quit and performing better.[33]Improving internal mobility is great for overall morale, spreads diversity throughout your organization, and helps you attract more candidates to new roles by displaying diversity in senior management.

Use a data-backed method to reduce inequality in STEM by switching to skills-based hiring

STEM has a diversity problem. Marginalized groups encounter educational and workplace obstacles that stop them from developing STEM skills and pursuing STEM careers. A robust commitment from organizations to create systemic change and use skills-based hiring and development can help address these issues. A skills-based approach is more inclusive and effective, from outreach and hiring to upskilling and promoting. To learn more about using skills-based hiring to address inequality, read our blog about closing the gender employment gap.You can also read our tips for creating a flexible working policy to ensure your work environment is as inclusive as possible.Or, if you’re already rolling out your inclusive hiring efforts and want to take them to the next level, use TestGorilla’s talent assessment platform to screen and hire the best.

Sources

“2022 Developer Survey”. (2022). Stack Overflow. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2022/#demographics-ethnicity-prof

“The STEM Labor Force of Today: Scientists, Engineers, and Skilled Technical Workers”. (2019). National Science Foundation. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20212

Fry, Richard; Kennedy, Bryan; Funk, Cary. (April 1, 2021). “STEM Jobs See Uneven Progress in Increasing Gender, Racial and Ethnic Diversity”. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/04/01/stem-jobs-see-uneven-progress-in-increasing-gender-racial-and-ethnic-diversity

“Persons with disability”. (2019). National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21321/report/persons-with-disability

Cech, Eric; Pham, Michelle V. (2017). “Queer in STEM Organizations: Workplace Disadvantages for LGBT Employees in STEM Related Federal Agencies”. MDPI. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/6/1/12

“LGBT Climate in Physics: Building An Inclusive Community”. (March 2016). APS Physics. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.aps.org/programs/lgbt/upload/LGBTClimateinPhysicsReport.pdf

Cech, Eric A; Waidzunas, TJ. (January 15, 2021). “Systemic inequalities for LGBTQ professionals in STEM”. Science Advances. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abe0933

“Study Furthers Understanding of Disparities in School Discipline”. (June 14, 2022). National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/research-highlights/2022/study-furthers-understanding-of-disparities-in-school-discipline

Fry, Richard; Cilluffo, Anthony. (May 22, 2019). “A Rising Share of Undergraduates Are From Poor Families, Especially at Less Selective Colleges”. Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/05/22/a-rising-share-of-undergraduates-are-from-poor-families-especially-at-less-selective-colleges/

“Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics – 2022”. (February 23, 2023). Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf

Sansone, Dario; Carpenter, Christopher. (November 18, 2020). “Turing’s children: Representation of sexual minorities in STEM”. PLOS ONE. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0241596

“Engaging females in STEM”. (November 2017). International Technology and Engineering Educators Association. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.iteea.org/File.aspx?id=137392&v=2ae3e75c

“Science Performance”. (2022). National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cne

“Role models vital in keeping European girls’ STEM interest alive”. (April 25, 2018). Microsoft. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://news.microsoft.com/europe/2018/04/25/role-models-vital-in-keeping-european-girls-stem-interest-alive/

Matysiak, Sarah. (September 15, 2022). “STEM students with disabilities face extra barriers in earning degree”. Badger Herald. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://badgerherald.com/news/2022/09/15/stem-students-with-disabilities-face-extra-barriers-in-earning-degree/

Malik, Aisha. (March 8, 2023). “Elon Musk apologizes after publicly mocking Twitter employee with disability”. TechCrunch. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://techcrunch.com/2023/03/08/elon-musk-apologizes-after-publicly-mocking-twitter-employee-with-disability/

“The Talent Shortage”. (2022).ManPowerGroup. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://go.manpowergroup.com/talent-shortage

Agarwal, Pragya. (December 3, 2018). “Unconscious Bias: How It Affects Us More Than We Know”. Forbes. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/pragyaagarwaleurope/2018/12/03/unconscious-bias-how-it-affects-us-more-than-we-know/?sh=3333fe6e13e7

Kline, Patrick; Rose, Evan; Walters, Christopher. (July 2021). “Systemic Discrimination Among Large U.S. Employers”. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.nber.org/papers/w29053

Sundaram, Khyati. (March 13, 2022). “‘Skills-Based’ Hiring Driving 70% Increase In Senior Role Hires For Women Hired”.The HR Director. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.thehrdirector.com/business-news/diversity-and-equality-inclusion/skills-based-hiring-drives-a-70-increase-in-the-number-of-women-hired-for-senior-roles/

Bourke, Juliet. (January 22, 2018). “The diversity and inclusion revolution: Eight powerful truths”. Deloitte Review. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/deloitte-review/issue-22/diversity-and-inclusion-at-work-eight-powerful-truths.html

Douglas, Ray. (November 14, 2018). “Lack of diversity increases risk of tech product failures”. The Financial Times. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/0ef656a8-cd8a-11e8-8d0b-a6539b949662

“2019 Retention Report”. (2019). Work Institute. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://info.workinstitute.com/hubfs/2019%20Retention%20Report/Work%20Institute%202019%20Retention%20Report%20final-1.pdf

“Upskilling’s impact on learning, talent retention, and talent acquisition”. PwC ProEdge. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://proedge.pwc.com/upskilling-and-talent-strategies

“Closing the STEM Gap”. (2017). Microsoft. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://query.prod.cms.rt.microsoft.com/cms/api/am/binary/RE1UMWz

“IBM SkillsBuild for Academia”. IBM. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://skills-academy.comprehend.ibm.com/

Deming, David; Noray, Kadeem. (June 2019). “STEM Careers and the Changing Skill Requirements of Work”. Harvard University. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/ddeming/files/dn_stem_june2019.pdf

“The Emerging Degree Reset”. (February 2022).The Burning Glass Institute. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.burningglassinstitute.org/research/the-emerging-degree-reset

Fuller, Joseph, et al. (October 2017). “Dismissed by Degrees”. Harvard Business School. (Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.hbs.edu/managing-the-future-of-work/Documents/dismissed-by-degrees.pdf

“6 trends impacting women in STEM”. (July 11, 2022). Handshake Blog. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://joinhandshake.com/blog/employers/trends-impacting-women-in-stem/

Praslova, Ludmila. (June 21, 2022). “An Intersectional Approach to Inclusion at Work”. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://hbr.org/2022/06/an-intersectional-approach-to-inclusion-at-work

“Flexible working options are no longer regarded as an added benefit”. (2022). s|three . Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://www.sthree.com/en-gb/insights-and-research/how-the-stem-world-works/2022/flexible-working/

Somers, Meredith. (April 12, 2022). “Women are less likely than men to be promoted. Here’s one reason why”. MIT Sloan. Retrieved June 27, 2023. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/women-are-less-likely-men-to-be-promoted-heres-one-reason-why

Related posts

Hire the best candidates with TestGorilla.

Create pre-employment assessments in minutes to screen candidates, save time, and hire the best talent.

Latest posts

The best advice in pre-employment testing, in your inbox.

No spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Hire the best. No bias. No stress.

Our screening tests identify the best candidates and make your hiring decisions faster, easier, and bias-free.

Free resources

Anti-cheating checklist

This checklist covers key features you should look for when choosing a skills testing platform

Onboarding checklist

This resource will help you develop an onboarding checklist for new hires.

How to find candidates with strong attention to detail

How to assess your candidates' attention to detail.

How to get HR certified

Learn how to get human resources certified through HRCI or SHRM.

Improve quality of hire

Learn how you can improve the level of talent at your company.

Case study: How CapitalT reduces hiring bias

Learn how CapitalT reduced hiring bias with online skills assessments.

Resume screening guide

Learn how to make the resume process more efficient and more effective.

Important recruitment metrics

Improve your hiring strategy with these 7 critical recruitment metrics.

Case study: How Sukhi reduces shortlisting time

Learn how Sukhi decreased time spent reviewing resumes by 83%!

12 pre-employment testing hacks

Hire more efficiently with these hacks that 99% of recruiters aren't using.

The benefits of diversity

Make a business case for diversity and inclusion initiatives with this data.